Keynote Address by CJI N.V. Ramana at ISMS2021

17th July 2021

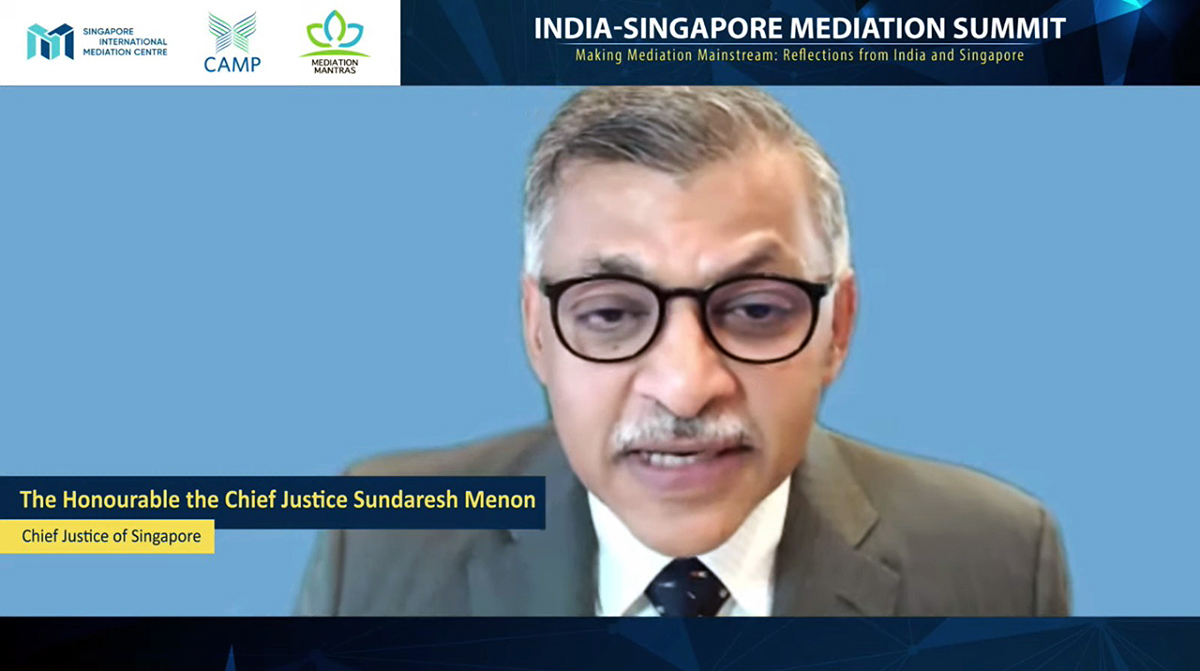

Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon - Chief Justice of Singapore, at India - Singapore Mediation Summit 2021

Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon

Setting the Stage for Mediation’s Golden Age

Saturday, 17 July 2021

The Honourable the Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon

Supreme Court of Singapore

The Honourable Mr Justice N. V. Ramana, Chief Justice of India

Mr Edwin Tong SC, Minister for Culture, Community and Youth, and Second Minister for Law, Singapore

Mr Amitabh Kant, Chief Executive Officer of the NITI Aayog

Mr George Lim SC, Chairman of the Singapore International Mediation Centre

Honourable Judges and Distinguished Members of the Bar from India, Singapore, and elsewhere

Distinguished Guests

Ladies and Gentlemen

A very good afternoon.

It is my privilege to deliver the keynote address for today’s Summit, alongside the Honourable Chief Justice Ramana. Before I begin, let me first extend my heartiest congratulations to Chief Justice Ramana on his recent appointment as the 48th Chief Justice of India. This is a signal achievement as well as a tremendous responsibility, and we all wish you the very best in your tenure. As Your Lordship had mentioned, it was a real pleasure to have had a substantive online meeting with you some weeks ago, and I look forward to working together on a number of the initiatives between our courts that we discussed.

Let me also, like Chief Justice Ramana, acknowledge the efforts of our mutual friend and colleague, Justice A K Sikri, on promoting the excellent relations between the legal establishments of India and Singapore. And one sign of that relationship can be seen in the fact that less than two weeks ago, I had the immense pleasure of presiding at a hearing of the Court of Appeal of Singapore from a decision of the Singapore International Commercial Court (“SICC”), where Justice Sikri shared the bench with me and three other colleagues.

The theme for today’s event is international commercial mediation. As a means of resolving disputes, mediation has a long and storied history, perhaps especially in Asia. While arbitration has taken the spotlight for some time, owing in large part to the adoption of the New York Convention more than six decades ago in 1958, in recent years mediation has come to experience real growth as a key mechanism for the resolution of cross-border commercial disputes. This trend bears particular significance for all of us here because a robust and trustworthy system of dispute resolution is integral to the strong ties in trade and commerce that exist between our jurisdictions.

Investors and businesses need this confidence as they venture afield. And so, I propose to use my time to share with you some reflections on the rapid march of mediation into the mainstream of dispute resolution, its immense potential for Asia, and the role that our jurisdictions may play in this development.

The revival of mediation and the Singapore Experience

I begin by outlining Singapore’s journey and experience with mediation, which I suggest can best be understood in three main arcs.

First Arc: A Rekindled Interest

The first begins in the 1990s, when we made a deliberate decision to revive what was then the somewhat fading practice of mediation. Mediation, of course, is not a new phenomenon. Historically, India and Singapore share a tradition of village elders and respected community leaders resolving disputes through informal mediation. In India, for instance, as Minister Edwin Tong mentioned in his opening speech, this was among the responsibilities vested in the village panchayat boards. In post-independence Singapore, as the country underwent rapid urbanisation, this simple but often effective method of dispute resolution gradually gave way to formal court litigation.

The concerted move to revive the practice of mediation was driven by four main objectives: first, to check the growing trend of litigiousness that was taking hold in our society; second, to provide a more economical and less adversarial way to resolve conflicts and in this way to enhance access to justice; third, to ease the judicial caseload; and fourth, to promote recourse to amicable and harmonious means of conflict resolution, which we saw as being consistent with our culture and values.

These objectives rested on the growing recognition of the unique value and benefits that mediation promises. By now, these are familiar to most of us. Foremost among them is the fact that the parties can resolve their disputes through a tailored process in a flexible yet confidential manner, while also having to expend less time and money when compared to other more formal modes of dispute resolution.

As Chief Justice Ramana observed, it features the unique and considerable advantage of bringing to the inside of the process, those who have traditionally been outsiders despite having the most to lose. It is also highly effective – more than 70% of mediated disputes are settled, often within a day, and this is so even for the more complex, cross-border commercial cases.

Even in situations where settlement might prove elusive, the parties having undergone mediation are clearer as to the issues and interests at stake, and so are better able to tailor and streamline subsequent processes to manage the outstanding issues in the best way possible. Importantly, mediation, being non-adversarial and interest-based, can help preserve a functional relationship between disputing parties. In jurisdictions such as ours where a premium is placed on harmony, trust, and good relationships, mediation’s ability to enable parties to manage and resolve their differences, without taking adversarial and overly hostile positions that result in zero-sum win-loss outcomes, cannot be understated.

We therefore took steps in the 90s to establish a formal structure for mediation within the domestic legal landscape. In 1994, alternative dispute resolution (“ADR”) was officially introduced in the then-Subordinate Courts, now known as the State Courts, to promote and facilitate non-adversarial methods of dispute resolution.

In 1997, we established the Singapore Mediation Centre (“SMC”) that focused on dealing with commercial disputes and with promoting the use of mediation outside of the court system.

From 1998, we took this a step further by establishing, in locations throughout the country, Community Mediation Centres (“CMCs”) designed to provide an accessible, affordable, and effective means of resolving community conflicts. Drawing lessons from the past, mediators at these CMCs were community volunteers and most of them were leaders of community and grassroots organisations.

These concerted and sustained efforts have contributed significantly to the successful revival of mediation within the domestic legal landscape. In the process, we have come to appreciate once again the features and value of mediation, and have developed a corps of professionals familiar with its use.

Today, mediation is facilitated and encouraged at all levels of the court system and in respect of a wide range of matters, whether involving commercial interests or those of the community. Between 2012 and 2017, some 6,700 cases were mediated annually at the State Courts, with a settlement rate in excess of 85% . Working in tandem with the SMC, cases in the Supreme Court are also regularly assessed for their suitability for referral to mediation.

Second Arc: Towards Maturity and Internationalisation

Our domestic experience paved the way for the second arc of our journey, which has been defined by the growth and internationalisation of our mediation services and institutions. The genesis of this is a high-level Working Group that was formed in 2013 to recommend ways to develop Singapore as a centre for international commercial mediation. The Working Group, which comprised local and international luminaries in the field, observed that with the exponential growth in trade and investment across Asia, demand for dispute resolution services that were attuned to and able to cope with the growing complexity of cross-border commercial disputes would inevitably also rise.

Two key reforms were implemented pursuant to the recommendations of the Working Group. First, in 2014, we established the Singapore International Mediation Centre (“SIMC”) as a private, non-profit organisation with the specific objective of providing world-class international commercial mediation services. Although the SIMC is still a relatively young institution, it has to date received more than 170 mediation filings involving parties from nearly 40 jurisdictions, with a total dispute value exceeding US$4.4 billion. Second, we introduced the Mediation Act in 2017 which forms the cornerstone of our mediation framework. Apart from clarifying common law rules of confidentiality and admissibility in the context of mediation, and allowing parties to seek a stay of court proceedings pursuant to an agreement to mediate, the Act also provides, among other things, for the enforceability of out-of-court mediated settlements in the same manner as an order of court.

This is vital if we are to promote the willingness of parties to engage in the process of mediation and to ensure that they adhere to the terms of any mediated settlement agreement.

Our dispute resolution landscape today offers users a full suite of options: the SICC for cross-border commercial litigation, the Singapore International

Arbitration Centre (“SIAC”) for international arbitration, and the SIMC for mediation. And it is fair to say that mediation has taken its rightful place as a co-equal and complementary process alongside the more entrenched options of litigation and arbitration.

Third Arc: Entering mediation’s golden age

What then is third arc of our mediation journey? In a sense, it is a work in progress. I recall that in September 2019, when addressing an audience in Vietnam, I expressed the belief that in the coming decade, as the global economic order continues to reorient itself towards Asia, we would see the dawning of a new, golden age of international commercial mediation.

Taking in the developments that have occurred in the short period that has passed since then, I suspect that this might happen even sooner.

In particular, there are two drivers that provide fuel and momentum as we embark on the third arc – first, the Singapore Convention on Mediation (“the Singapore Convention”) and second, the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keynote Address by Justice Sundaresh Menon, Chief Justice of Singapore, at India - Singapore Mediation Summit 2021

The Singapore Convention is poised to radically alter the future of mediation, not just in Singapore, but globally. Minister Edwin Tong spoke briefly about this earlier in his address. The most important contribution of the Singapore Convention is the confidence it provides that international commercial mediation can result in binding and internationally enforceable outcomes. In so doing, it alleviates a key concern that has long acted as a drag on the growth of mediation as compared to other adjudicative mechanisms – namely, the perception that mediated outcomes are, in the end, simply fresh agreements that are just as violable as the agreements that gave rise to the disputes in the first place. In the international survey conducted by the Singapore International Dispute Resolution Academy (“SIDRA”) and published last year, enforceability was identified as the top factor influencing the respondents’ choice of dispute resolution mechanisms. The survey found that while users valued mediation for conferring speed and cost advantages over other modes of dispute resolution, it lost its edge when it came to enforceability. With the Singapore Convention in place, users can now have the best of both worlds: speed and cost savings, with wide-spread enforceability. This is a compelling proposition for businesses seeking to lower the legal risks of their international ventures and investments while also containing their expenditure.

The 54 countries that have signed the Singapore Convention so far already include some of the largest economies in the world – the US, China, and India, among others. Just last month, Brazil joined their ranks as the latest signatory to the Convention. Six of these, including Singapore, have ratified or approved the Convention. There will naturally be a gestation period for any international Convention as significant as this. But I am confident that with time, the Singapore Convention will become as influential and widely accepted as the New York Convention, which governs the enforcement of arbitral awards in more than 160 countries. Indeed, the Singapore Convention has already sparked renewed discussions on the role that mediation can play in other areas of dispute resolution, including Investor-State dispute settlement. The International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (“ICSID”), for instance, is working on institutional mediation rules tailored for investment disputes, and in March this year, entered into a Memorandum with the SIMC to explore further collaboration in this area.

Brazil became a signatory in June 2021. See, for the purpose of the agreement and a summary of key provisions, I suggest the other key driver that will fuel the growth of mediation is the COVID-19 pandemic. Just months after the Singapore Convention opened for signing, the world became gripped in the throes of the pandemic, which has caused unprecedented disruptions to all aspects of life and commerce. Entire industries have been left grappling with the uncertainties arising from disrupted supply chains, delayed payments, and operational difficulties. For many caught in this situation, it makes little commercial sense to seek a vindication of their legal rights as though nothing had changed. Formal and adversarial means of dispute resolution almost always entail the expenditure of higher legal costs and time, while also carrying the risk of alienating the very same long-term business relationships that are going to be critical for business recovery. And even if one prevails in such proceedings, there is no guarantee in these times that the losing party will be able to pay any damages that might be awarded.

In these circumstances, mediation offers considerable advantages as a means of helping businesses steer their way through the uncertainties brought about by the pandemic. We have therefore made a concerted effort to encourage even greater reliance on mediation during this period. For domestic matters, for instance, the Supreme Court worked with the SMC to launch the SGUnited Mediation Initiative.

The scheme provided for the referral of suitable cases in the Supreme Court to the SMC for mediation with the parties’ consent and at no charge. Not only did this assist many of the parties to settle their disputes quickly and amicably and focus on the more urgent priority of running their businesses, it also helped the courts manage the backlog of matters that had arisen in the wake of the lockdowns brought about by the pandemic. In all, mediation was conducted under the scheme for more than 100 cases, of which around 40% were successfully settled. And this resulted in substantial savings of trial days that would otherwise have been taken up in the High Court.

For international matters, the SIMC also introduced the COVID-19 Protocol in May 2020. Under the Protocol, mediations could be organised within 10 days and conducted at reduced fees. The Protocol also lays down procedures for online mediation, in response to the travel restrictions imposed across nearly all major jurisdictions. Further, the Protocol provides that mediated outcomes will be enforceable either as court orders under the Mediation Act or the Singapore Convention in countries that have ratified or approved the treaty. The Protocol has been well-received internationally and remains in force to date.

If the Singapore Convention helped to raise awareness of and confidence in mediation, the COVID-19 pandemic has catalysed a greater willingness to undertake mediation and, in this process, to discover its real value as an efficient, effective, and enforceable mechanism for dispute resolution. I understand, for instance, that compared to 2019, the SIMC’s caseload in 2020 nearly doubled. And its caseload for the first half of 2021 is already almost that of the whole of last year.

This, I suggest, is a clear sign that mediation is fast gaining momentum especially in the resolution of international commercial disputes. When one considers the other factors at play, including the rise of Asian corporates, our cultural affinity for mediation, and a growing appreciation for the inherent value of dispute prevention and containment, it seems reasonable to suggest that we stand today at the cusp of mediation’s golden age.

III. Brief Reflections on the Future of Mediation

As we look ahead to the future of mediation, we should remind ourselves that legal services – as with all other services – must ultimately be designed with the user at the heart. And for international mediation to come into its own, it must meet the evolving needs of cross-border businesses. I suggest, in this light, that two trends will likely shape mediation’s future.

The first is that, at least in the near term, the real attraction of mediation will lie in its inherent flexibility and consequent ability to complement, rather than compete with, litigation and arbitration. This too was a point noted by Chief Justice Ramana. While mediation might well come to thrive as a standalone dispute resolution mechanism, especially as the enforceability of mediated outcomes ceases to be a factor with the growing acceptance of the Singapore Convention, the current state of its reception suggests that its popularity is at the highest when deployed in combination with other adjudicative methods.

In a recent 2021 International Arbitration Survey, 59% of the respondents expressed a preference for using arbitration in combination with other forms of ADR, such as mediation, to resolve cross-border commercial disputes. This was a significant increase over the corresponding figure in the 2018 survey at 49% and the 2015 survey at 34%.

This clearly suggests a growing demand for holistic and tailored dispute resolution frameworks that are able to operate in an integrated way, matching the right type of procedures to the right type of disputes.

Such a preference has implications for the way we design our legal systems and processes, and this is reflected in the offerings of our dispute resolution institutions in Singapore. In the SICC, for instance, the Practice Directions provide among other things that counsel should take instructions prior to the first Case Management Conference on their client’s intention and willingness to proceed with mediation or any other form of ADR, and that if they are agreeable to mediate, the Judge may give directions pertaining to the timelines for and conduct of the mediation. 18 Where the parties are not prepared to mediate, the Judge may direct that the issue be reconsidered at a later stage. Similarly, the Arb-Med-Arb Protocol that was developed by the SIAC and the SIMC, has been gaining popularity. Under the Protocol, once the notice of arbitration has been filed, proceedings are immediately stayed to enable the parties to engage in mediation within an eight-week window.

Further provisions ensure that the parties can shuttle easily between mediation and arbitration, or litigation, at any stage and in any order. The central goal is to ensure that the parties have the best option – or mix of options – suited for the resolution of their particular dispute.

The second trend we can anticipate, perhaps in the longer term, is the greater integration of mediation into our legal systems as a means of serving the rule of law. While mediation is largely an out of court process, it is a misconception to suggest that mediation hurts the rule of law by taking the law out of the hands of the courts. Rather, the rule of law requires that there be effective access to justice, and this can take place outside the confines of a courtroom.

By enhancing the prospect of achieving final and acceptable outcomes when disputes arise, and by providing an often more timely and cost efficient alternative to the other methods of dispute resolution, mediation offers a real and vital option in helping to address legal needs that might otherwise go unmet. We can see this in our experience with the use of mediation during the pandemic as it offered the parties a more conciliatory and expeditious option of dispute resolution that was better suited to their priorities in a challenging period. Indeed, in the aftermath of the pandemic, there is value in considering the formalisation and expansion of some of these mediation programmes that will help us manage and alleviate the court’s caseload.

Furthermore and importantly, to come to a point alluded to by Mr George Lim in his opening remarks, mediation also holds the potential to transform society’s notions of justice from an adversarial, hierarchical, and formal process geared towards zero-sum outcomes, to one that is more consensual, flexible, and interest-based, and thus more open to outcomes that focus on the parties moving forward constructively. For many types of disputes including corporate restructuring, family and community disputes, and the significant number of complex commercial matters that have an underlying relational element, mediation offers a particularly effective and compelling mechanism for parties to resolve their conflicts on their own terms, in a manner that prevents the further deterioration of fractured relationships, and where the costs imposed by the process are amply justified in relation to its benefits. The point in the final analysis is that access to justice entails a fair resolution of the dispute, and this need not come only through an adjudicative process.

Concluding remarks

I want to close by speaking very briefly about the role that India and Singapore can play in encouraging the revival and growth of mediation. As most of us will be familiar, the India-Singapore economic corridor is fast growing and an extremely important one in Asia and in the world. Minister Edwin Tong had earlier shared some statistics on the size and growth in foreign direct investment between our two countries. On a similar note, bilateral trade in goods and services has also grown by over 80%, from S$20 billion in 2005, to S$38 billion in 2019.

Our strong economic relations and our shared affinity for conciliatory methods of dispute resolution suggest that we can be a testbed for innovation in this field, and collaboratively work to promote mediation as part of a more modern dispute resolution system that could serve as a model for Asia and the world.

Chief Justice Ramana raised a number of difficult and thought-provoking questions towards the end of his address, and this could be something that professionals from both our jurisdictions come together to study and consider responses to. India evidently shares our interest in mediation as a critically important process of dispute resolution, and has in recent years introduced various initiatives to promote its use in a cross-border commercial context, including through the signing of the Singapore Convention.

The SIMC and its strategic partners in India have also been working with various stakeholders on projects intended to take cross-border mediation in India and Singapore to the next level. As we stand at the cusp of mediation’s golden age, broader and deeper collaboration between our countries in this area will best position our people, our legal professionals, and our businesses to benefit from its rise in this new era.

Finally, I extend my heartfelt appreciation to the organisers of this Summit, who have had to manage the event despite the uncertainties and challenges posed by the pandemic. The success of today’s event stands as a testament to their dedication and hard work over the past months.

Thank you all very much, and I wish you and your families safety and good health in these challenging times.

This Keynote Address, was delivered by the Honourable Chief Justice of Singapore, the Honourable Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon, on 17th July 2021, at the India - Singapore Mediation Summit (ISMS2021).

Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon acknowledges his colleagues, Assistant Registrars Kenneth Wang and Reuben Ong, for all their assistance in the research for and preparation of this address.

ISMS2021 was organised by Singapore International Mediation Centre (SIMC), in strategic partnership with CAMP Arbitration & Mediation Practice, and Mediation Mantras.